Craig Hardgrove

Oh, those crazy brits! It’s amazing how almost every time I find work being done (either making an actual game or doing a research project) on science and video games, it’s based in the UK. Is it also a coincidence that any good music I’ve come across in the past 5-10 years has also come from UK artists?…. but I digress.

I recently came across an article posted on museum-id.com. The site is essentially the web-based home for new ideas in museum curation and public education. They’ve had quite a bit of success with their web-based game High Tea, in which you play a British smuggler of opium and tea in the 1830′s. The game creators worked closely with experts in this field to add just the right about of historical accuracy to the game. It turned out that the history of this subject, as is often the case, is rife with issues surrounding the politics and ethical issues of the opium trade, particularly in China. The game drew in so many players with it’s gameplay that many became interested in learning more about and discussing the Opium Wars. Just the right amount of historical accuracy actually added an additional level of intrigue to the story that players of the game found themselves drawn to find out more about the real history surrounding the game’s story.

I can’t help but think of Bioshock, where I’m certain that at least a handful of people decided to pick up Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged or The Fountainhead after hearing so much in-game discussion about free markets, capitalism, and the political ideas of libertarians. Bioshock took an idea fundamentally grounded in philosophical and political thought and thoroughly expounded upon it. I would argue that the game world was made infinitely more rich by basing its fundamental ideology and story behind a real-world idea that the player could actually go read about. In this way, the story of Bioshock entered the real world and could become a starting off point for further reading and discussions.

A real bug caught in amber which you could totally probe for some DNA

Take another example, this time more related to science. Would Jurassic Park have been nearly as cool if they never showed you how to genetically engineer a dinosaur by extracting DNA from prehistoric mosquitos caught in amber? That is an actual scientific idea (that doesn’t work… yet) that non-scientists who watched the movie realized wasn’t even science fiction… they were left asking, “Wait, why don’t scientists just do that?” And if they found the answer, they might learn something about DNA, biomedical engineering, or the ancient Earth in the process.

So what does this have to do with science in video games? … everything. You add a dash of the real world to a video game and that realism is enough to propel the game’s message directly to the hearts and minds of the player, because the player will establish their own connections to those ideas.

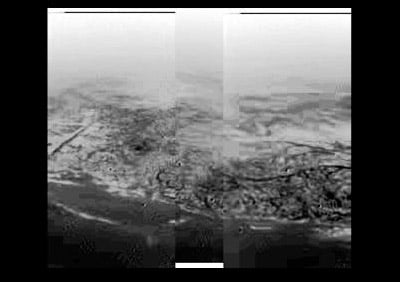

Rivers and lakes of methane on the surface of Saturn's moon, Titan, reconstructed from images acquired by the Cassini-Huygen's lander during it's descent to the surface.

View from the surface of Titan, as seen from the Cassini-Huygen's lander.

So if your game is set on Titan, why not start it off showing the actual descent and landing images from the Cassini-Huygens probe that landed on the surface. Players will know that it’s real, not necessarily because they’re familiar with the images, but because it will seem real… because it is. Better yet, set your game on Mars where we have hundred of thousands of real images of the surface. We can construct 3D terrain models for some of the really interesting places (more on this in a future post). There are countless numbers of images that can be used in this way.

3D view, constructed from real topography of Mars, of Valles Marinaris.

There is a wealth of data out there that scientists have access to, both for the Earth and other planets, which could be integrated into video games to add to the sense of realism. I hope that in my future writings, I can convince you that some of the bits I know about could add a bit of a “science-themed backdrop” to a video game… for example, in addition to 3D digital terrain models, there are data sets available that will allow you to make your proportions of rocks to dirt (using thermal inertia images) more realistic based on your geologic setting, or to make the colors and layers of rocks look realistic by making maps of spectral parameters (using near-infrared absorption bands) you can’t see with your naked eye. Like the makers of High Tea, game developers will hopefully see that the scientific community is a resource for drawing players into their game world by tying the game world to the real world.